Article courtesy of Devon G. Peña

|

Roberto Bedoya for Creative Time Reports | Tucson, Arizona | September 16, 2014

Intervening in discussions about gentrification and placemaking, cultural activist Roberto Bedoya champions the creative resilience found in communities of color—and exemplified by the Chicano practice of Rasquachification—to suggest “placekeeping” as a strategy for advancing racial justice goals.

I grew up in a working-class barrio called Decoto, in San Francisco’s East Bay. My neighbors were the Trianas, who had painted their house hot pink. I loved it. The Trianas’ house was across the street from the grounds of the Catholic church. Many of the Anglos who lived in the new tract homes being built around my barrio parked their cars in front of the house on Sunday, and I recall how they would speak ill of it as they made their way to church. For them the house was too bright. But for me the brightness represented Rasquache—an aesthetic of intensity that confronted our invisibility, our treatment as less than.

In the mid-1960s the state of California—in order to build a freeway through what it considered blight—decided to condemn the small houses in our barrio. It could not see that each one was unique and full of character, with features like a nopal cactus fence, a porch decorated with papel picado or anarchic rose gardens that overtook the yards. The community organized itself to defend our barrio through public hearings and petitions and a lawsuit filed by the Raza Unida Party. We stopped the freeway.

When I think back on that time now, it is clearer to me that what we were confronting was the “white spatial imaginary,” an antiseptic ethos that effectively deemed being poor and of color as civic imperfections to be expunged. A spatial imaginary that is historically rooted in the development of public policies that created restrictive covenants excluding Jews, African-Americans and other communities of color from neighborhoods circumscribed as enclaves of whiteness. A spatial imaginary that persists today, in discriminatory policies and practices that disproportionately affect communities of color, such as New York City’s stop-and-frisk tactic, Florida’s stand-your-ground law or the reckless militarized policing in Ferguson, MO.

Rasquachification messes with the white spatial imaginary and offers up another symbolic culture—combinatory, used and reused.

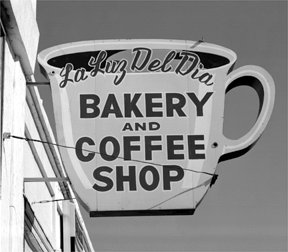

This is what the white spatial imaginary means: if you’re a person of color standing on a corner, beware. You are perceived as a threat because your color challenges the white spatial imaginary of that street. Your whistler is a threat; your homeboy style is a threat; your hip-hop, mariachi or Chinese opera music is a threat. What’s more, the mosque is a threat; the abortion clinic is a threat; the queer community youth center is a threat; even the independent storefront business, with its hand-painted signage, is a threat. What Ferguson reveals is that walking down the street is grounds to harass colored boys like me cuz our gait, our skin, our style is a blemish on the white spatial imaginary that needs to be arrested or eradicated—one way or another erased.

Last year I found myself speaking at a conference in Baltimore where discussions about the changing nature of cities were dominated by the topic of gentrification. As I presented a talk on the politics of belonging and dis-belonging as they relate to practices of “creative placemaking,” I drifted away from my consideration of artists as placemakers to ask the audience who among them knew the term Rasquache. No hands were raised. I then pivoted and said that I was not interested in unpacking how gentrification operates; instead I wanted to talk about how places are made through Rasquachification. As the gentry moves the working class and poor out of cities, what unsanctioned means will the newly displaced residents use to style their next locale? How might this form of artistic expression, this form of speech, provide a counterframe to gentrification and the homogenizing aesthetic of the white spatial imaginary?

|

A flowerpot that you would never find at Home Depot

|

The scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto describes Rasquache as a Chicano aesthetic with an “attitude rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability yet mindful of stance and style.” Evoking rasquachismo from an artist’s perspective, Amalia Mesa-Bains calls it “the capacity to hold life together with bits of string, old coffee cans, and broken mirrors in a dazzling gesture of aesthetic bravado.” When I think of rasquachismo, I think of repurposing a tire into a flowerpot that you would never find at Home Depot. Such an object signifies the imaginary structured by resourcefulness, and prompted by poverty, which is distinct from the imaginary imposed by the monetization of neighborhoods, a prevailing objective in urban development.

Rasquachification messes with the white spatial imaginary and offers up another symbolic culture—combinatory, used and reused. The Rasquache spatial imaginary is the culture of lowriders who embrace the street in a tempo parade of coolness; it’s the roaming dog that marks its territory; it’s the defiance signified by a bright, bright, bright house; it’s the fountain of the peeing boy in the front yard; it’s the DIY car mechanic, leather upholsterer or wedding-dress maker working out of his or her garage with the door open to the street; it’s the porch where the elders watch; and it’s the respected neighborhood watch program. Rasquachification challenges America’s deep racial divide through acts of ultravisibility undertaken by those rendered invisible by the dominant ideology of whiteness.

Rasquachification is also what the community activist Jenny Lee calls placekeeping—not just preserving the facade of the building but also keeping the cultural memories associated with a locale alive, keeping the tree once planted in the memory of a loved one lost in a war and keeping the tenants who have raised their family in an apartment. It is a call to hold on to the stories told on the streets by the locals, and to keep the sounds ringing out in a neighborhood populated by musicians who perform at the corner bar or social hall.

At a moment when cities are rapidly being transformed, I worry that the people proposing and implementing policies are not thinking about spatial justice. That the speech of the poor and of communities of color is not heard in part because of a devaluation of an expressive aesthetic—the speech of life in all its Rasquache glory, which is saying I’m city and which does not jibe with the entitlement of the white spatial imaginary that dominates the understanding of the public sphere.

The Rasquache spatial imaginary is a composition, a resourceful admixture, a mash-up imagination that says, I’m here.

Policy and imagination condition each other, and a dialectical relationship between the two is necessary to preserve the vibrancy of our cities. Currently, urban policymaking is determined by the drive to accumulate as much capital as possible, and the effect is to destabilize our cities through the displacement of individuals, families and entire communities. But the people who shape communities from the ground up—the urban residents who practice the art of poiesis, or making in the sense of transforming the world—should have the real agency. Acts of imagination ultimately shape the public sphere, where we make meaning together, in shared space. Imagination produces a commons that is continually generated and mutated through our actions. Both the imagination that engendered the pink tire flowerpot and the policies behind zoning ordinances ultimately affect how a city speaks—the sounds of the city, the shape of its buildings, the unit of the block, the voices of the people who live there, their poetics. The poetics and praxis of a city bring into being livability.

Often when I participate in placemaking/placekeeping discussions, what pops into my mind are a few literary references related to cities. I hear the metaphorical laments of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (“it used to be”) or the conjurations of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (awe: the new city) in these passionate internal monologues. I think of Gabriel García Márquez’s Macondo, where imagination enriches the day-to-day; Macondo, with its local pulses of civic life, where the Rasquache spatial imaginary—the aesthetic of making something out of nothing, of the discarded, irreverent and spontaneous—is alive; Macondo, where out of realness emerges the magical.

The Rasquache spatial imaginary is a composition, a resourceful admixture, a mash-up imagination that through objects and places says, I’m here—whether that be New Orleans, East L.A., the Bronx or South Tucson—and I’m part of the many and I walk down these streets with a Rasquache passport that says I belong.

Evidence |

Photo by Kaucyila Brooke, Rasquachification by Reuben Roqueñi.

|